Amy Evelyn Tomes Private Grief, Public Denial? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Every one of Itteringham St Mary’s gravestones is a memorial to a life, not just a record of a death. Every one tells a story of some sort if only we attempt to find it. Here is one such story, albeit one only about the closing stages of a life.

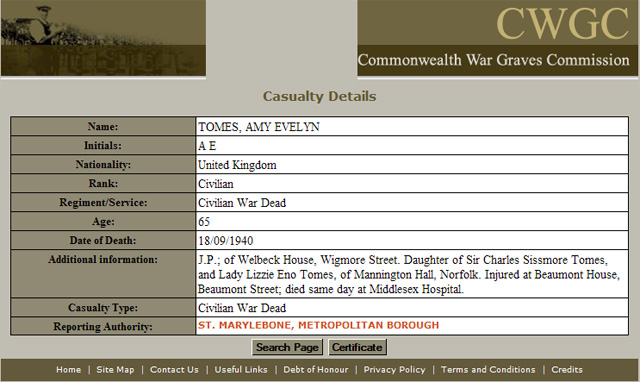

Had you read The Times on Saturday 21st September 1940 you might have spotted the death notice for Amy Evelyn Tomes JP, the only daughter of Sir Charles Sissmore Tomes and Lady Lizzie Eno Tomes both deceased and formerly of Mannington Hall. ’The funeral will be held at Itteringham, Norfolk at 12:30 pm on Thursday September 26th’. You would have read that she died ‘on September 18th suddenly and peacefully’.

There is nothing here to indicate how she died and villagers may not have known for some time. The Eastern Daily Press reported her death and funeral on 27th September and at least commented that she had been ill, had been operated on and the London hospital she was in was hit by a German raider. But it goes on to say that she was removed to a nursing home where she died. The cause and timing of death was unstated. Now we know, courtesy of her gravestone E040, later erected in matching style to that of her father and mother in Itteringham churchyard E061, that she was ‘killed by enemy action, September 17th 1940’.

This confirms when she died and makes clear where the incident happened. It also gives her place of death as the Middlesex Hospital not a nursing home. What was happening in London at that time? For months Londoners had been expecting much worse than the intermittent bombing attacks on the capital. This period of so-called ‘phoney war’ led to preparations for large scale bomb damage. In early September 1940 Hitler ordered the start of a massive bombing blitz on London as a softening up precursor to ‘Operation Sealion’ the invasion of England. The blitz started in earnest on Saturday 7th September 1940 and the first major period of attacks was to last for 57 nights in a row with some daylight raids in addition [Constantine Fitzgibbon: The Blitz].

Damage and loss of life was substantial. On 12th September a bomb hit St Paul’s Cathedral, but did not explode and was successfully removed a few days later. On the 13th Buckingham Palace was deliberately targeted and hit. But the RAF fought back against the Luftwaffe daytime raids and with particular success on 15th September. On the 17th Hitler, as emerged later, cancelled Operation Sealion – such was the effect of the RAF’s success and the positive morale with which Londoners withstood the attacks. But the bombing continued.

During the day on the 17th the raids were quite light. But that night saw a heavy raid. 268 bombers dropped 334 tons of high explosive and 391 incendiary canisters on London. The 18th saw the last big daylight raid of 70 bombers in 3 waves of which 19 were shot down for the loss of 12 fighters. That night was the heaviest raid yet with 300 bombers, 350 tons of HE and 628 incendiaries.

So Amy Tomes died within the first fortnight of the blitz and on a night of heavy bombing in central London. Indeed so atypical was the night of the 17th that the next day The Times wrote an article commenting on the severity of the bombing and the hits in the main shopping areas of Oxford St, Bond St, Berkeley Square and Savile Row. This was a notable article as the impact of the bombing was not written about that often and not in detail – a far cry from today’s media coverage of war and terrorist outrage. The media then were severely restricted as to what could be reported for fear of helping the enemy and of damaging civilian morale.

This restriction on newspaper coverage means that the local papers are of little help in exploring specific incidents. For example the Marylebone Mercury (copies held on microfilm at The City of Westminster Archives Centre, St Anne’s St, W1) would have covered that area, but on Saturday 21st it ran a rather mild article reviewing the week’s bombing with merely a few photos of apparently relatively minor suburban damage. No mention of central London damage. No other local papers were published for this area during the war.

Nonetheless we have been able to piece together a good idea of what happened. The Westminster Archive holds the files of the St Marylebone Civil Defence Unit. Their file for incident 75 contains handwritten notes written in the control room of all the incoming and outgoing messages directing rescue operations. The more or less minute by minute notes are worth quoting at length as they give us an evocative and moving picture of the unfolding of the incident and at least some of its devastating impact.

And so it continues. Ambulances are called for. People are trapped on a second floor. A demolition squad is requested to help free the man buried. And then:

Between midnight and one o’clock it becomes clear that the incident is bigger than at first thought. More personnel and rescue units are sent. Captain Davis is sent to take charge. People are trapped on the top floor and a longer ladder is requested [this is almost certainly for the six story Beaumont House]. At 01:15 the mortuary van is sent to collect bodies. A few minutes later it is reported that 14 stretcher cases so far have been removed. Not until 02:30 is it reported that a long ladder is on its way. The control room is not clear throughout on the number of casualties. But at 02:54 a second depot is called on for assistance in digging out a casualty and 20 casualties and 3 dead are reported.

Through the early hours various of the rescue units return to base. Just after 05:00 a request goes out to the Borough to clean debris outside 34/35 Devonshire Place [meaning Devonshire St as Devonshire Place around the corner seems not to have been hit and is a very wide street with 34/35 well away from the incident] as soon as possible as it is the only route available for use or traffic.

This is despatched at 08:51 on the morning of the 18th. This sounds like the end of the incident but the log has more yet.

Subsequent problems abound. Control does not know where the wounded were taken. Three former residents of 34 Devonshire St (just round the corner and hit by one of the bombs) ask when they can salvage their personal effects. Later on the 18th a strong smell of coal gas is reported from Devonshire St and personnel in the vicinity are requested not to smoke! The electricity department is notified that exposed lights are burning and the rescue party are unable to extinguish. But by the end of the 18th the incident seems over. However, at around 5 am on the 19th there is a sudden flurry of enquiries worrying that there may be a delayed action bomb – a feature of the blitz. Reassurance that the search found nothing is issued. The clear up continued. Suddenly, on the 21st of September:

The confusion of the times and the pressure of handling a constant flow of new incidents is made clear a few days later by enquiries about where survivors were evacuated to. On the 22nd:

Even in January and May 1941 the incident log was busy. Number 34 Devonshire St was reported unsafe and rescue parties (complete with mobile canteens each day) were sent, no doubt on demolition duties. And so the file ends.

From later sources (Available in Westminster Archives: a brief 1955 published History of King Edward VII Hospital Sister Agnes, built after the war on the site of Beaumont House) we know that at least one of the 3 high explosive bombs was a parachute mine that landed on Beaumont House. Another bomb hit 34 Devonshire St and demolished it. The third may well have hit the Duchess Nursing Home more or less adjacent to Beaumont House.

The King Edward VII Hospital history is interesting. Founded in 1899 by Fanny and Agnes Keyser it looked after Boer War officer casualties at 17 Grosvenor Crescent, then at Grosvenor Gardens and then back at the Crescent.

Sister Agnes

Given royal patronage it thrived as a charitable venture. However it could not find suitable evacuation premises in 1940 and could not stay open during the blitz. It was closed in 1940. Its original home was bombed in 1941 and Agnes died later that year not having recovered from the shock of the destruction of her own home and the adjacent hospital site. But the charity remained intact and attracted her legacy and other donations, although no hospital operated for the rest of the war. The history of the hospital continues:

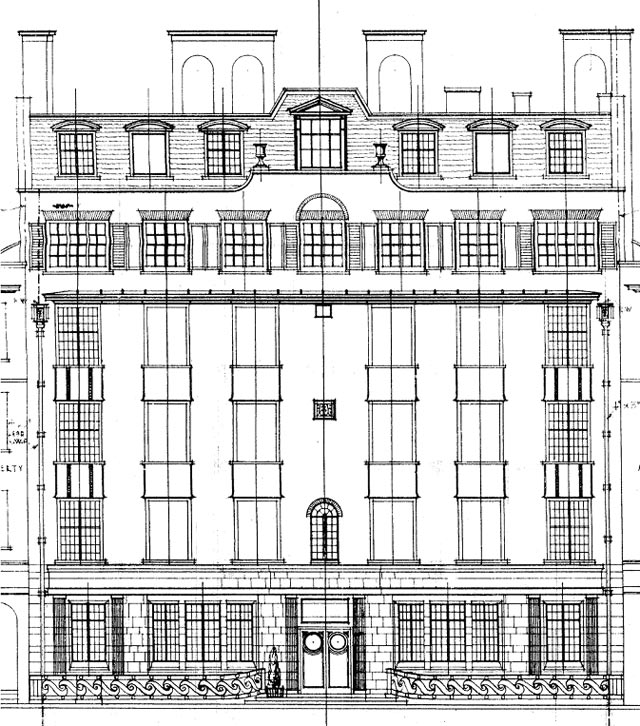

We are lucky to find not only this reference, but also to find that the complete original 1930 set of architect’s drawings for the construction of Beaumont House are preserved in Westminster Archives (WDP2/317 has the drawings of Wm. A. Pite, son and Fairweather of 12 Carteret St, Queen Anne’s Gate, SW1). They detail the whole building, including its steel frame construction, and show the elevation of the front:

The architect’s plan of the front elevation of Beaumont House for its construction in 1930

What is striking is that the 1948 rebuilding followed the original design remarkably closely. The small rounded arch detail above the central fourth floor windows can be seen on both the 1930 plans and the photo of the building today. The bay windows for the three main floors are very distinctive. Of course the modern hospital has gone through progressive expansion into both numbers 11 and 12 to the north (or left) and numbers 5 to 7 to the south. But today’s hospital is a strong likeness to the 1930s Beaumont House.

Beaumont Street today showing the King Edward VII Hospital built on the site of numbers 5 to 12 Beaumont Street. The design of the façade is very similar to the original 1930 design of Beaumont House.

The rebuilt 34 and 35 Devonshire Street

34 and 35 Devonshire Street to the left of the scaffolding with the end (numbers 11 and 12) of the modern Beaumont Street Hospital on the left

Devonshire Place from Devonshire St, with Dr Rawlins’ number 28 down towards the end on the left

Well, remember Amy Tomes?

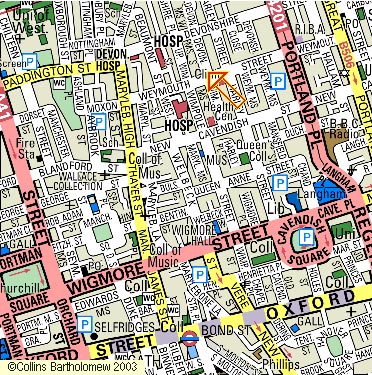

Why was she caught up in the bombing of Beaumont House? We know she lived at number 13 Welbeck House, Wigmore Street, the family’s London home for many years. It seems that this block on the junction of Wigmore and Welbeck streets was not war damaged and the apartment block of 20 homes is still there, even if the retail premises at street level are a little different.

Welbeck House, Wigmore Street

This had been the London home of her father Sir Charles Sissmore Tomes at his death in 1928 and she continued to live in number 13. The Dictionary of National Biography and Who’s Who tell us that Amy came from a prestigious medical family with her father and grandfather knighted for medical practice – both Sir Charles and Sir John were eminent dental surgeons. What she did as a career we do not know, but it is possible that she was engaged in hospital activities in some way too. The EDP obituary and burial notice for Sir Charles mention in passing that Amy was at one time before 1928 a member of the London County Council. Her own notice only tells us that when resident at Mannington Hall she had taken a great interest in the church and social activities of the district.

Why was she at Beaumont St on the night of the bombing? It seems she was a patient recovering from an operation – whether the operation was done there or elsewhere we do not know. The manager of the Beaumont Street Hospital was a Miss Duncanson. She was the architect’s client in 1930 and the manager in 1940, the sole resident listed in Kelly’s. Not only that but she was a JP too. So here we have a magistrate colleague and possibly a friend of Amy Tomes running the Beaumont Street Hospital. Intriguingly a J. Duncanson sent flowers to Amy’s mother’s funeral in Itteringham in 1935. It seems a distinct possibility that Miss Duncanson was a friend of the family and her hospital would be Amy’s natural choice for an operation and recuperation.

Nothing else about the incident has yet been discovered except that on Tuesday 24th September The Times Classifieds carried this announcement:

Miss Duncanson wishes to thank everyone who has written to her and stood by so loyally and rendered such real service to all her staff in this disaster. As she is still in hospital and not encouraged to write she hopes they will understand her not thanking them individually.

Even in this the true nature of the event was disguised. It would of course be interesting to know much more about the life and work of Amy Tomes. Further research continues.

Copyright © Maggie and William Vaughan-Lewis |

A postscript to the above article comes via an email from Stephen G. Peart Senior. His father was gardener at Mannington and he writes:

For a great many years my father, Harold Peart, tended the Tomes' graves. He had been charged to do so and corresponded, annually, with Miss Duncanson in London. She paid him a small remuneration for his work and he responded each Christmas by sending her a box of Norfolk holly. (He was in the business of floral tributes, wreaths, etc) This continued, certainly, beyond 1954 although we had left our Itteringham home in 1947. I think the arrangement ceased when Miss Duncanson passed on.

My father was a gardener at Mannington Hall for 17 years before being called into the Royal Air Force for war service in the Medical Corps. Those 17 years took him through the Tomes residency to a later occupant, Commander C R Sharp RN (who I believe was also a man of medicine).

I note from the 1901 census that 24yr old Amy Tomes has no occupation listed. I also can vividly recall being told that Amy was "blown to bits" during a London air raid.

My family roots are in Itteringham where my grandfather George was the last Peart to be resident in the village. He died October 1954.

My father's time with the Tomes family must have been good as we had a photographic portrait of Mrs Tomes at Mannington, (or it could have been Amy) hanging in the house. Sadly, it was lost during moves of more than 40 years ago.

Your research on the subject is phenomenal. I regret not questioning my father on this period in his life but at that time nothing was more distant from my mind. |